When looking at ‘hyperpop,’ it’s easy to lump artists under the glitchy, overindulgent, and ‘hyper’ soundscape that’s been linked to the genre. However, when looking at the cultural and ‘Pop’ connotations of this new moment in music, the question posed by artist Charli XCX is pointed. She asks her Twitter fans, “What is Hyperpop?”1

In the general sense, ‘Hyperpop’ is a genre that was created in the UK in the early 2010s through a label called PC Music. The genre is defined as a “Maximalist and deconstructed approach to pop music.” Due to artists such as SOPHIE, Hannah Diamond, and Charli XCX, the genre eventually reached the modern mainstream in the early 2020s; as both a serious, solitary genre, and as backing tracks on short-form content platforms, such as TikTok and Instagram.2

However, when attempting to pinpoint the soul of the genre, the implications of ‘Hyperpop’ become complicated. Starting with aesthetics, it’s simple to spot the links to ‘Hyper.’ Artists such as SOPHIE create a symphony of electronic bliss with tracks like Ponyboy, establishing a frenzy of sound that fits the mold of ‘Hyper’ to a T. On the contrary, when looking at the aesthetics behind the word ‘Pop,’ things become a bit more unclear. There are certainly instances of the ‘Pop’ aesthetic in ‘Hyperpop,’ with lyrical motifs from artists like Charli XCX, exploring common themes like nostalgia or a radio-friendly structure, especially on tracks like Apple–giving more credibility to the idea that the two genres are linked. However, when looking deeper into the aesthetics of ‘Pop,’ the motifs connecting the two quickly fall apart. Historically, ‘Pop,’ as a genre, has been concerned with cuteness and softness, with artists like Taylor Swift, Olivia Rodrigo, and Sabrina Carpenter fighting for a crown of non-obtrusiveness in the modern day. Their music is safe and accessible for a large audience regardless of age, politics, and casualty. This notion of ‘Pop’ struggles to fit in when compared to its self-imposed sub-genre, ‘Hyperpop,’ which historically doesn’t pretend to be for everyone; the genre is steeped in Queer and Trans culture, it’s energetic and abrasive, it’s most things that ‘Pop’ is not. I believe this to be where the two genres separate; in fact, I would question why they were considered joint in the first place.

Following this line of questioning, it’s important to look at what the genre and aesthetics of ‘Hyperpop ’ do for an artist’s image. Does it create a community of like-minded artists, or does it lump an unconventional sound into a forced sense of accessibility? Circling back to Charli XCX, she herself doesn’t consider her music to be a part of any genre-specific sound, stating on Twitter that “[she] doesn’t identify with music genres.”3 This push away from a defining genre seems to be a common theme throughout ‘Hyperpop’ discourse, with the multi-genre ‘Hyperpop’ artist Bladdee also expressing his opinion on the movement. Bladee mostly fixates on the fact that labels and genres limit music, especially when creating an experimental sound.4 This begs another question- who gets to define this sound: the artists who created the soundscape, or the industry which pushes it? Looking at streaming services like Spotify, one could argue that corporations continue to push the label of ‘Hyperpop,’ Glitchcore,’ and ‘Indie Electronica’ in an attempt to distance themselves from the musical roots the genre was founded upon. “Hyperpop is a simulation” is the tag that reads on Spotify’s ‘Hyperpop’ playlist, which launched in 2019, roughly. The playlist consists of new-wave artists like 100Gecs, Drain Gang, and Midwxst, all artists in their teens or early twenties, and all dispersed under the eclectic sound of the experimental internet. However, despite this isolation and distance of this sound, one thing this collective of online producers doesn’t connect to is the ‘Hyperpop’ label itself.

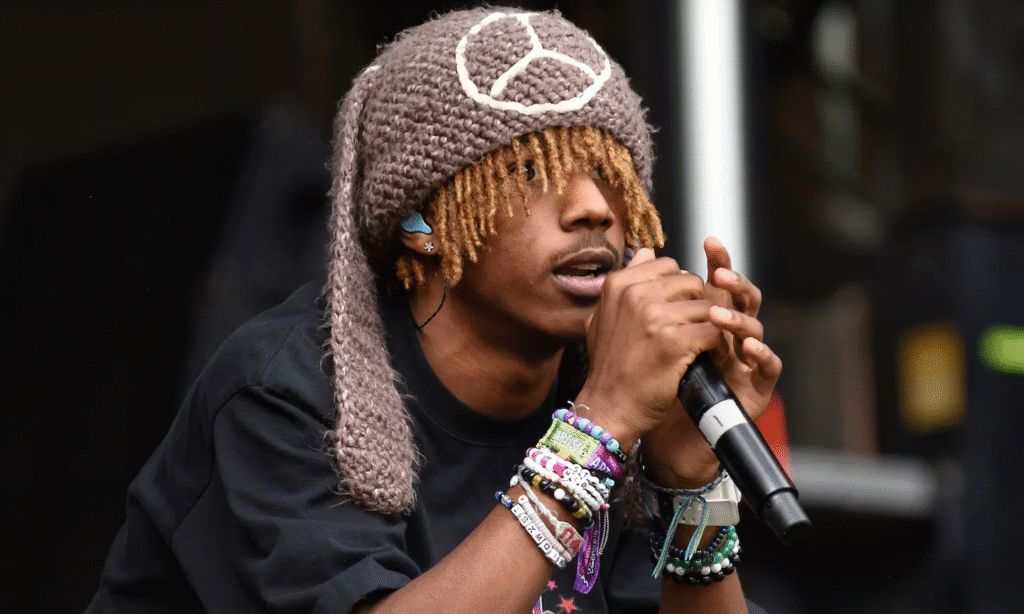

Midwxst, an 18-year-old breakout underground artist, spoke to this notion. His press release for his debut EP Back in Action, urges fans and critics alike not to fall into the trap of genre, “He’s part of this group of young kids leading this new subset of music… but he’s definitely not boxed into the hyperpop sound and on his new music he flows beyond the genre,”5 he says. Apple Music only serves to further confuse artists with its take on ‘Hyperpop,’ with the creation of a sound-specific playlist ‘Glitchcore,’ and yet another label that young creatives must adhere to remain relevant. However, it’s also important to acknowledge the value of corporations to artists seeking Hyperpop stardom. Without the corporate creation of these genres and playlists, many of the artists currently fighting for their own sound and representation would have gone undiscovered, continuing to make music in their bedrooms with little to no impact on modern-day discourse. Artists under the ‘Hyperpop’ umbrella, such as Midwxst and his colleagues, Angelus and D0llywood, all fall into this category. Yet they continue to fight for their own personal sound, with D0llywood saying to Dazed magazine: “We’re not PC Music, we’re not glitchcore. We’re hyper kids making pop. The pop is loud, it’s hyper.”6 The artists mentioned would eventually go on to create their own label/genre, Digicore, for young electronic producers to congregate under without the pressure of algorithms or corporate ties.

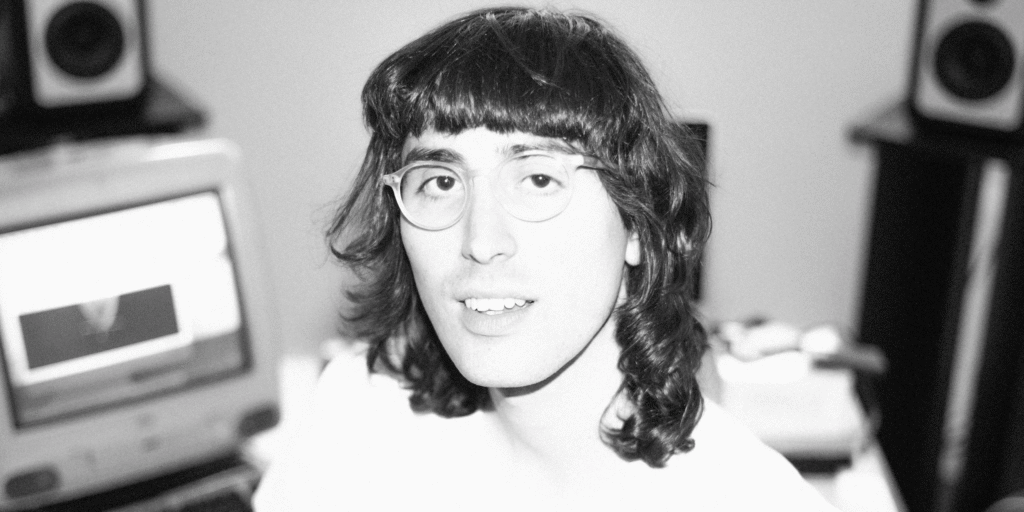

This redefining of genres is important to many of the newer generations of ‘Hyperpop’ musicians, but what about the purveyors of the genre? PC music was both a label and a musical genre created in the United Kingdom. The label served to prop up new-wave, queer, and experimental artists such as SOPHIE and Hannah Diamond, legends in the now ‘Hyperpop’ space. The label was a way forward for ‘Pop’ of the time with “PC Music [rejecting] a dark, murky underground electronic sound… [helping] define a new kind of pop.”7 The label, which had been operating for nearly 10 years under producer A.G. Cook, closed its doors in 2023, deciding to take on a more archival role after a string of slow-releasing albums. The label’s step back signaled the end of an era for the forerunners of the ‘Hyperpop’ genre. However, the label’s shutdown signaled an even messier slew of ‘genre-ism’ that infected PC roots across the board. The new-generation and the old-generation became, in the words of Pitchfork: “[a] Frankensteinian macro-genre, referring to an array of internet artists who down genres like cocktails and love the fuck out of Auto-Tune.”8 This cataclysm of genre and form has led to murky waters for the artists involved in the movement; as aforementioned, the new generation doesn’t assimilate, and the old generation is something else entirely. With this conflict between artist and genre on the brain, it’s time to address the question that Charli XCX posed: “What is Hyperpop?”

In short, ‘Hyperpoo’ is only a figment. As artists, new or old, push back against the label that confines them, one truly sees how fragmented the corporate idea of ‘Hyperpop’ is across the soundscape. ‘Pop’ itself is lost on artists within the ‘Hyperpop’ sphere. The cute and comfortable aesthetics of ‘Pop’ are thrown to the wayside in favor of aesthetics that match the individual artist. Whether that’s through SOPHIE’s visual dichotomy of the natural and unnatural, or Midwxst’s Y2K-inspired internet-core, these artists refuse to assimilate to what the genre asks of them. This isn’t to say that there aren’t sonic similarities, certainly parts of the present soundscape have both ‘Hyper’ and ‘Pop’-ism in some regards, but I believe that this label rejection goes one step further than just the sonic criticism of ‘Pop’ in ‘Hyperpop’. There has never been an attempt in PC music or Digicore–genres created by artists for artists-to mask opinions or be non-confrontational, yet when looking at ‘Pop,’ a large part of the genre’s aesthetic is conformity. With that being said, some might argue that it’s important to consider the visibility the genre-labeling of ‘Hyperpop’ as a label has given to artists who want to express their opinions, and to an extent, they are right. But to mistake the genre of ‘Hyperpop’ as all that can come from PC, Queer, and New-Gen musicians is a horrendous oversimplification of a budding non-conformist movement. When looking at Charli’s question of “what is Hyperpop?” I understand where her confusion about the label comes from. What do these artists at the forefront of modern music have in common with ‘Pop’? The short answer is nothing; they are not ‘Pop’ in any traditional sense, and forcing both new and old artists to conform under a “macro-genre” simply for the sake of accessibility and profit not only sucks the soul out of this new-age experimental music, but limits artists who wish to push the envelope forward.

- https://x.com/charli_xcx/status/1286007438416556032 ↩︎

- https://www.edmprod.com/hyperpop/ ↩︎

- https://x.com/charli_xcx/status/1286007438416556032 ↩︎

- https://www.dazeddigital.com/music/article/55293/1/the-rise-and-fall-of-hyperpop-the-internets-most-confusing-music-genre ↩︎

- https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2021/08/09/the-brash-exuberant-sounds-of-hyperpop ↩︎

- https://www.dazeddigital.com/music/article/55293/1/the-rise-and-fall-of-hyperpop-the-internets-most-confusing-music-genre ↩︎

- https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2021/08/09/the-brash-exuberant-sounds-of-hyperpop ↩︎

- https://pitchfork.com/features/article/the-lost-promises-of-hyperpoptimism/ ↩︎